Hanging out with the hippies

From the archives: writing for the Financial Times, I spent a week in the dreamy Indian pilgrimage town of Pushkar to find a colourful collision of cultures.

A teenage girl with wide eyes and pierced nose was being led by one arm down to the holy lake. A bearded sadhu with a bare chest pressed flowers, sweets and a few grains of rice into her hand. "This is the ancient puja ceremony," he said, thumbing a red dot onto her forehead.

"It's so cool," said the girl, who was called Caroline and was spending a year in India before her first term at Oxford. "Repeat after me," said the holy man. "I pray for health, happiness and success and I make a donation of 100 rupees." Caroline woke briefly from the spell. "100! How about 50?" The man suggested 60. "That's cool," she replied, with a wide smile.

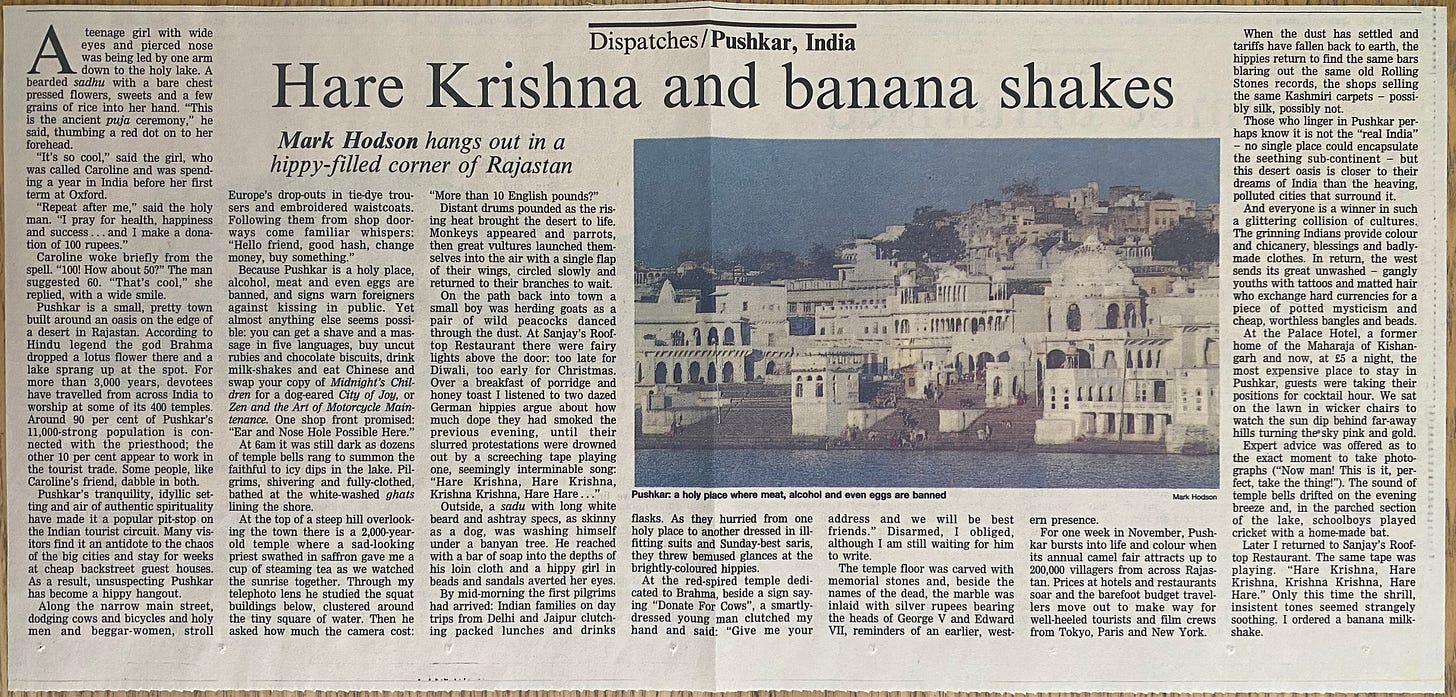

Pushkar is a small, pretty town built around an oasis on the edge of a desert in Rajastan. According to Hindu legend the god Brahma dropped a lotus flower there and a lake sprang up at the spot. For more than 3,000 years, devotees have travelled from across India to worship at some of its 400 temples.

Around 90 per cent of Pushkar's 11,000-strong population is connected with the priesthood; the other 10 per cent appear to work in the tourist trade. Some people, like Caroline's friend, dabble in both.

Pushkar's tranquility, idyllic setting and air of authentic spirituality have made it a popular pit-stop on the Indian tourist circuit. Many visitors find it an antidote to the chaos of the big cities and stay for weeks at cheap backstreet guest houses. As a result, unsuspecting Pushkar has become a hippy hangout.

Along the narrow main street, dodging cows and bicycles and holy men and beggar-women, stroll Europe's drop-outs in tie-dye trousers and embroidered waistcoats. Following them from shop doorways come familiar whispers. "Hello friend. good hash, change money. buy something."

Because Pushkar is a holy place, alcohol, meat and even eggs are banned, and signs warn foreigners against kissing in public. Yet almost anything else seems possible: you can get a shave and a massage in five languages. buy uncut rubies and chocolate biscuits, drink milkshakes and eat Chinese and swap your copy of Midnight's Children for a dog-eared City of Joy, or Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. One shop front promised: "Ear and Nose Hole Possible Here."

At 6am it was still dark as dozens of temple bells rang to summon the faithful to icy dips in the lake. Pilgrims, shivering and fully-clothed, bathed at the white-washed ghats lining the shore. At the top of a steep hill overlooking the town there is a 2,000-year-old temple where a sad-looking priest swathed in saffron gave me a cup of steaming tea as we watched the sunrise together.

Through my telephoto lens he studied the squat buildings below, clustered around the tiny square of water. Then he asked how much the camera cost: "More than 10 English pounds?"

Distant drums pounded as the rising heat brought the desert to life. Monkeys appeared and parrots, then great vultures launched themselves into the air with a single flap of their wings, circled slowly and returned to their branches to wait.

On the path back into town a small boy was herding goats as a pair of wild peacocks danced through the dust. At Sanjay's Rooftop Restaurant there were fairy lights above the door: too late for Diwali, too early for Christmas. Over a breakfast of porridge and honey toast I listened to two dazed German hippies argue about how much dope they had smoked the previous evening, until their slurred protestations were drowned out by a screeching tape playing one, seemingly interminable song: "Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare ..."

Outside, a sadhu with long white beard and ashtray specs, as skinny as a dog, was washing himself under a banyan tree. He reached with a bar of soap into the depths of his loin cloth and a hippy girl in beads and sandals averted her eyes.

By mid-morning the first pilgrims had arrived: Indian families on day trips from Delhi and Jaipur clutching packed lunches and drinks flasks. As they hurried from one holy place to another dressed in ill-fitting suits and Sunday-best saris, they threw bemused glances at the brightly-coloured hippies.

At the red-spired temple dedicated to Brahma, beside a sign saying "Donate For Cows", a smartly-dressed young man clutched my hand and said: "Give me your address and we will be best friends." Disarmed, I obliged, although I am still waiting for him to write.

The temple floor was carved with memorial stones and, beside the names of the dead, the marble was inlaid with silver rupees bearing the heads of George V and Edward VII, reminders of an earlier western presence.

For one week in November, Pushkar bursts into life and colour when its annual camel fair attracts up to 200,000 villagers from across Rajastan. Prices at hotels and restaurants soar and the barefoot budget travellers move out to make way for well-heeled tourists and film crews from Tokyo, Paris and New York.

When the dust has settled and tariffs have fallen back to earth, the hippies return to find the same bars blaring out the same old Rolling Stones records, the shops selling the same Kashmiri carpets - possibly silk, possibly not.

Those who linger in Pushkar perhaps know it is not the "real India" - no single place could encapsulate the seething sub-continent - but this desert oasis is closer to their dreams of India than the heaving, polluted cities that surround it.

And everyone's a winner in such a glittering collision of cultures. The grinning Indians provide colour and chicanery, blessings and badly-made clothes. In return, the west sends its great unwashed - gangly youths with tattoos and matted hair who exchange hard currencies for a piece of potted mysticism and cheap, worthless bangles and beads.

At the Palace Hotel, a former home of the Maharaja of Kishangarh and now, at £5 a night, the most expensive place to stay in Pushkar, guests were taking their positions for cocktail hour. We sat on the lawn in wicker chairs to watch the sun dip behind far-away hills turning they sky pink and gold.

Expert advice was offered as to the exact moment to take photographs ("Now, man! This is it, perfect, take the thing!"). The sound of temple bells drifted on the evening breeze and, in the parched section of the lake, schoolboys played cricket with a home-made bat.

Later I returned to Sanjay's Rooftop Restaurant. The same tape was playing. "Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare." Only this time the shrill, insistent tones seemed strangely soothing. I ordered a banana milkshake.

This article was originally published in the Financial Times in 1994. Copyright: Mark Hodson.

Photos: Pushkar Lake by Patrick Dawson. Creative Commons licence: CC by 2.0. Other images by the author.