Saigon, 1992: the most thrilling experience of my life in travel

The sheer luck of finding myself among the first independent travellers in Vietnam for 17 years, just as this extraordinary city exploded into life to celebrate a new year

Sometimes in life you just get lucky and find yourself in the right place at the right time. It was January 1992 and I’d been travelling around Thailand. My girlfriend had flown home to Amsterdam and I was at a loose end, drinking coffee, reading a copy of the Bangkok Post. I came across an article that said Vietnam had lifted its ban on independent travel: the communist government was now issuing 28-day visas and visitors could travel as they pleased, rather than being confined to official group tours.

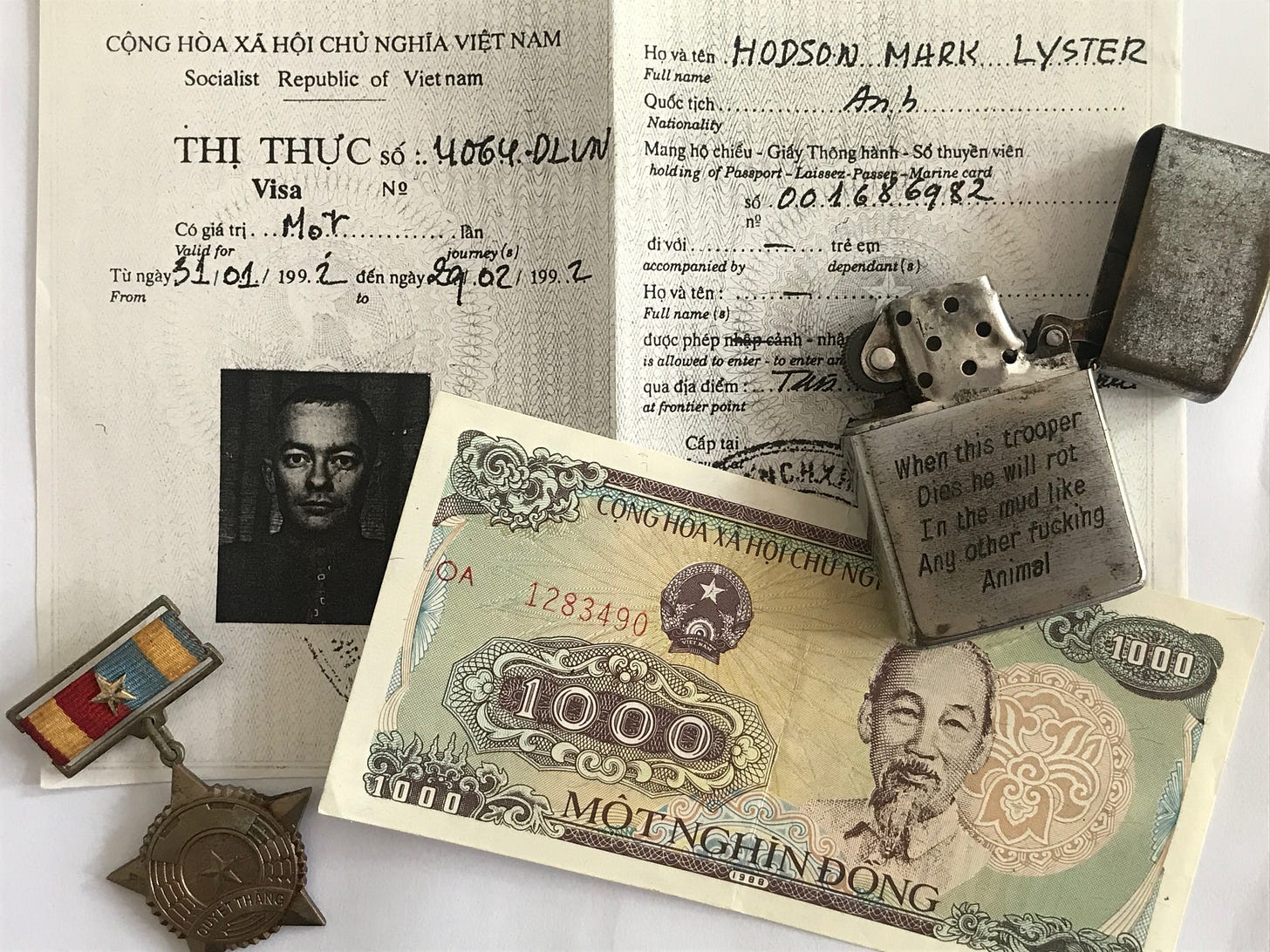

I paid a travel agent $150 for a one-way ticket to Saigon (several times today’s airfare) and $60 for a visa. Three days later I was on a half-full flight, surrounded mostly by Vietnamese men in suits, presumably party officials returning from shopping trips to Bangkok. I was seated next to Ken from Sweden, and we agreed to share a room.

We checked into a dilapidated Chinese hotel in the centre and strode out into the fading light to discover an elegant city of faded glamour and peeling paint fizzing with energy and excitement. Every square inch of pavement and road was jammed with people - cooking, slurping soup, buying, selling, shouting, laughing and, most of all, careering around on scooters, pushbikes and cyclos. By chance, we’d arrived on the evening before Tet, the Vietnamese celebration of Chinese New Year. As dusk fell, above the incessant beeping of horns, the fizz-bang of firecrackers broke out, the smell of cordite filling the sultry night air.

At the stroke of midnight, firecrackers strung from every doorway were lit and we were forced to stand in the middle of the road, fingers in ears, for a good 15 minutes. The fireworks continued through the night.

That week in Saigon was, and remains, the most thrilling experience of my travelling life. I don’t expect to witness anything like it again, but I’m just grateful I was there, at that moment in history when the Saigonese appeared to emerge from years under communism to embrace a hopeful new future, and stare - with mouths agog - at these newly-arrived, pale-skinned, big-nosed tourists

Some took us for Russians and glared. The first Vietnamese word we learned was Anh, meaning English, which caused smiles to break out everywhere. People invited us into their homes for coffee, fruit juice or bowls of pho. One man insisted on showing me his MGA sports car, which his father had bought in Hong Kong in 1960. A middle-aged woman operating a food cart winked at me and grinned: “No money, no honey”, perhaps a phrase she’d learned during the American war.

There were so few independent travellers in Saigon that we were soon all on speaking terms - or, at least, nodding terms. We’d meet up in small groups for drinks at the Majestic Hotel or breakfast at the ninth-floor restaurant of the Caravelle Hotel, served by waiters wearing white dinner suits. One evening we ate a lavish meal at the French restaurant, Maxims, where I ordered sole meunière and bananas flambé.

To pay the bills, we carried around fistfuls of 1,000 dong notes, like that scene in The Sopranos. It all seemed unreal: a week earlier we had been backpackers sleeping in hostels and flop houses; now we were living like VIPs.

Better still, we knew how lucky and privileged we were to be in this astonishing city at this unique moment in time. We talked about how other tourists would arrive, how the economy would adapt, how the Vietnamese people would slowly become less amazed by us, more jaded. How life would improve for them.

On New Year’s Day, we were debating the cost of a ride to Cholon with a group of cyclo drivers when a middle-aged man with a kind face came out of his house to translate. When we failed to agree on a price, he invited all four of us inside for tea, which quickly became lunch - a delicious bowl of noodles followed by watermelon - sitting around a large table with his wife, children, sister and brother-in-law.

Fluent in French and English, the father had been held captive for eleven years at an American-run prison island and now belonged to the people’s committee in charge of District 1. His brother-in-law, who spoke English with a beautiful accent, owned a building company that employed 50 men. In the New Year he planned to buy a $9,000 Toyota.

It was 4pm by the time we left, with a lengthy round of handshakes, smiles and New Year wishes. The photo I took of the family is one of the items I’d rescue from a burning house.

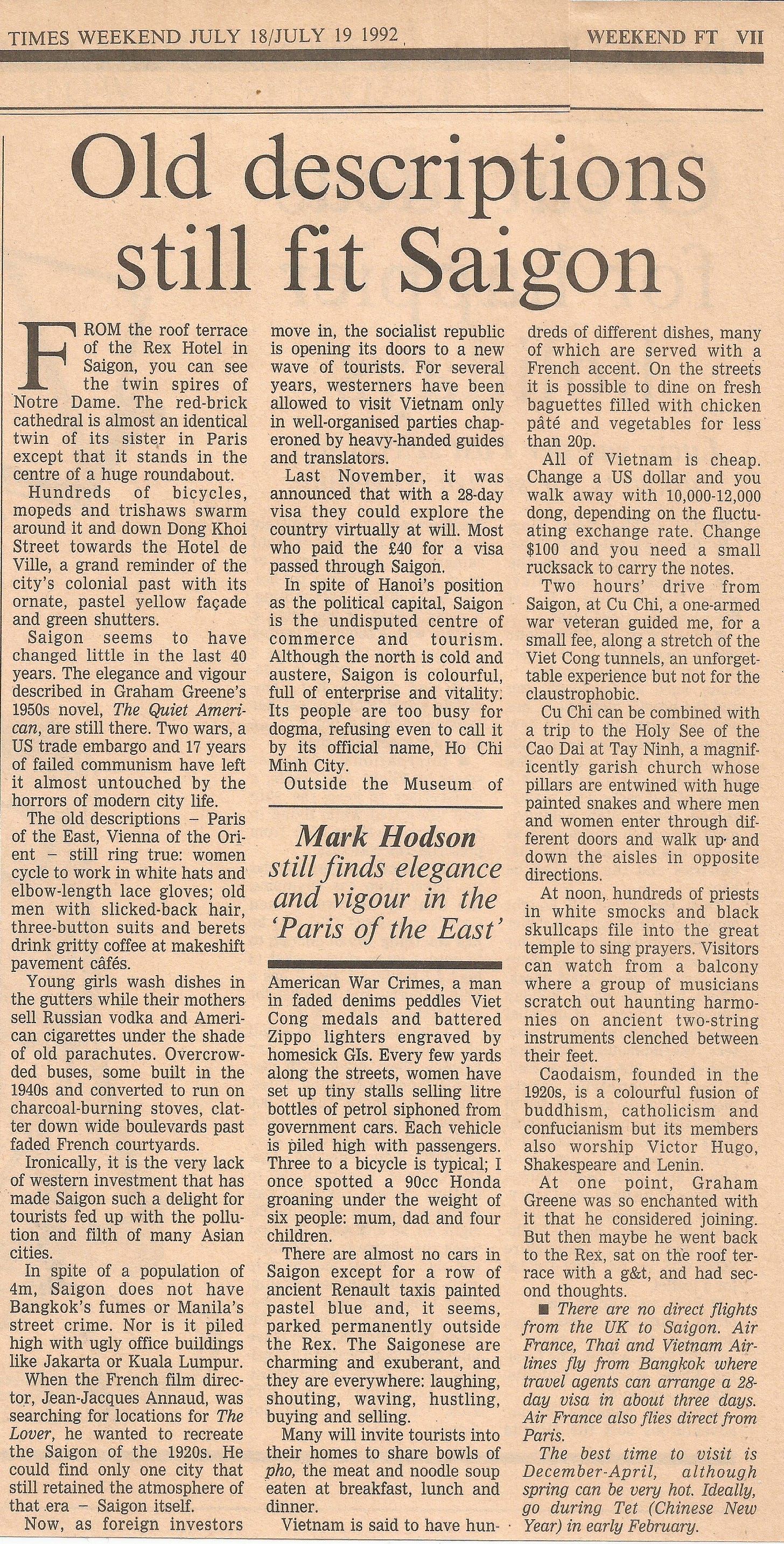

I wrote a dispatch about Saigon for the Financial Times which was published in the summer of 1992. It didn’t quite capture the sheer crazy exuberance and joyous chaos of the city, and it now seems embarrassingly gauche to have evoked the ghost of Graham Greene.

However, there are some pleasing details that anchor the city in that time: the women cycling to work in white hats and elbow-length lace gloves; the old men with slicked-back hair, three-button suits and berets; and the total absence of cars “except for a row of ancient Renault taxis painted pastel blue and, it seemed, parked permanently outside the Rex Hotel”.

At the same time, I was laughably ignorant of Vietnamese culture. I didn’t even know that the baguettes filled with pâté and vegetables were known as bánh mì, now a staple of global cuisine. I was ingenuous, naive. But as the great travel writer Pico Iyer wrote: “Wide eyes are, if nothing else, quite open.”

Here’s the FT piece reproduced in full. Please note: I wasn’t responsible for writing that headline.

Old descriptions still fit Saigon

From the roof terrace of the Rex Hotel in Saigon, you can see the twin spires of Notre Dame. The red-brick cathedral is almost an identical twin of its sister in Paris except that it stands in the centre of a huge roundabout. Hundreds of bicycles, mopeds and trishaws swarm around it and down Dong Khoi Street towards the Hotel de Ville, a grand reminder of the city's colonial past with its ornate, pastel yellow facade and green shutters.

Saigon seems to have changed little in the last 40 years. The elegance and vigour described in Graham Greene's 1950s novel, The Quiet American, are still there. Two wars, a US trade embargo and 17 years of failed communism have left it almost untouched by the horrors of modern city life.

The old descriptions - Paris of the East, Vienna of the Orient - still ring true: women cycle to work in white hats and elbow-length lace gloves; old men with slicked-back hair, three-button suits and berets drink gritty coffee at makeshift pavement cafes. Young girls wash dishes in the gutters while their mothers sell Russian vodka and American cigarettes under the shade of old parachutes.

Overcrowded buses, some built in the 1940s and converted to run on charcoal-burning stoves, clatter down wide boulevards past faded French courtyards. Ironically, it is the very lack of western investment that has made Saigon such a delight for tourists fed up with the pollution and filth of many Asian cities.

In spite of a population of 4million, Saigon does not have Bangkok's fumes or Manila's street crime. Nor is it piled high with ugly office buildings like Jakarta or Kuala Lumpur. When the French film director, Jean-Jacques Annaud, was searching for locations for The Lover, he wanted to recreate the Saigon of the 1920s. He could find only one city that still retained the atmosphere of that era - Saigon itself.

Now, as foreign investors move in, the socialist republic is opening its doors to a new wave of tourists. For several years, westerners have been allowed to visit Vietnam only in well-organised parties chaperoned by heavy-handed guides and translators. Last November, it was announced that with a 28-day visa they could explore the country virtually at will. Most who paid the £40 for a visa passed through Saigon.

In spite of Hanoi's position as the political capital, Saigon is the undisputed centre of commerce and tourism. Where the north is cold and austere, Saigon is colourful, full of enterprise and vitality. Its people are too busy for dogma, refusing even to call it by its official name, Ho Chi Minh City.

Outside the Museum of American War Crimes, a man in faded denims peddles Viet Cong medals and battered Zippo lighters engraved by homesick GIs. Every few yards along the streets, women have set up tiny stalls selling litre bottles of petrol siphoned from government cars. Each vehicle is piled high with passengers. Three to a bicycle is typical; I once spotted a 90cc Honda groaning under the weight of six people: mum, dad and four children.

There are almost no cars in Saigon except for a row of ancient Renault taxis painted pastel blue and, it seems, parked permanently outside the Rex. The Saigonese are charming and exuberant, and they are everywhere: laughing, shouting, waving, hustling, buying and selling. Many will invite tourists into their homes to share bowls of pho, the meat and noodle soup eaten at breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Vietnam is said to have hundreds of different dishes, many of which are served with a French accent. On the streets it is possible to dine on fresh baguettes filled with chicken pâté and vegetables for less than 20p.

All of Vietnam is cheap. Change a US dollar and you walk away with 10,000-12,000 dong, depending on the fluctuating exchange rate. Change $100 and you need a small rucksack to carry the notes.

Two hours' drive from Saigon, at Cu Chi, a one-armed war veteran guided me, for a small fee, along a stretch of the Viet Cong tunnels, an unforgettable experience but not for the claustrophobic. Cu Chi can be combined with a trip to the Holy See of the Cao Dai at Tay Ninh, a magnificently garish church whose pillars are entwined with huge painted snakes and where men and women enter through different doors and walk up and down the aisles in opposite directions.

At noon, hundreds of priests in white smocks and black skull caps file into the great temple to sing prayers. Visitors can watch from a balcony where a group of musicians scratch out haunting harmonies on ancient two-string instruments clenched between their feet.

Caodaism, founded in the 1920s, is a colourful fusion of Buddhism, Catholicism and Confucianism but its members also worship Victor Hugo, Shakespeare and Lenin. At one point, Graham Greene was so enchanted with it that he considered joining. But then maybe he went back to the Rex, sat on the roof terrace with G&T, and had second thoughts.

All photos are by the author, taken in 1992. You may also enjoy this collection of images at Saigoneer.com taken around the same time.

Sounds like an amazing moment in history to visit!

Good story - but actually the country opened to independent travelers a bit earlier. I flew Bangkok-Saigon with a friend in April 1990. We had mountain bikes and rode a significant portion of the 1000 miles of Highway 1 from Saigon to Hanoi, taking buses in between the riding segments. On one occasion the cops didn’t want us riding out of a small town where we had spent the night and made us get on a bus. Our only guides were a map of the country and some handwritten notes we had copied in Bangkok from some travelers who had just returned from Bangkok and who we met in Khao San Road. Good times!